Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Supreme Court nominations represent one of a president’s most consequential responsibilities, the impact of which extends decades beyond his term. The language presidents employ when discussing nominees reveals their constitutional philosophy, political strategy, and vision for the court. It is not clear when another Supreme Court seat will open. But, in anticipation of such a vacancy, this article examines how Presidents Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Donald Trump described Supreme Court justices and nominees during their campaigns and in official speeches.

This reveals that recent presidents (even from the same party) have used Supreme Court nomination rhetoric to signal fundamentally different visions of the court’s role: Obama emphasized professional excellence tempered by empathy, Trump foregrounded originalism and ideological transparency, and Biden focused on democratic legitimacy and concrete rights protections. These rhetorical patterns show that nominations are not framed merely as personnel choices, but as long-term constitutional and political commitments aimed at mobilizing distinct audiences and shaping how the court is understood by the public.

What I looked at

To conduct this analysis, I drew on various sources, including presidential debate transcripts, official White House statements and speeches, campaign materials, and verified news transcripts. I then analyzed these using several quantitative and qualitative methods.

A quantitative lens

How the presidents described the candidates

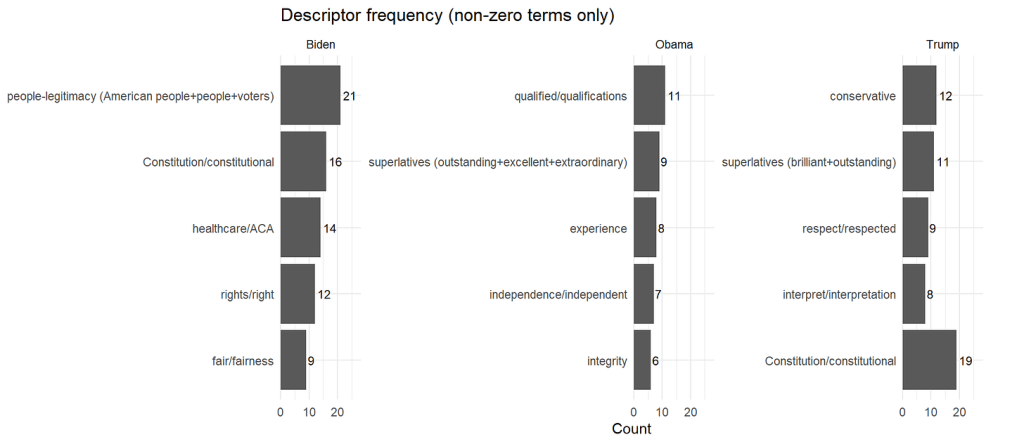

My analysis of nomination-related speeches revealed several distinct vocabularies. Out of all three presidents, Obama focused the most on traditional credentialing language – that is, how qualified the nominee was for the position. Specifically, he frequently used the words “qualified” or “qualifications” (11 times), followed by superlative descriptors such as “outstanding,” “excellent,” and “extraordinary” (nine times combined). Particularly important to Obama was to stress the nominees’ “experience” (eight times), “independence,” (“independence” or “independent” was mentioned in seven times), and “integrity” (six times). In doing so, he focused on competence, consensus, and professional credentials.

Trump’s vocabulary, on the other hand, signaled his expectation of high-caliber nominees that would also hold a particular judicial philosophy. He used “Constitution” or “constitutional” most often (19 times), followed by “conservative” (12 times) and the combined superlatives “brilliant” and “outstanding” (11 times). Additionally, Trump emphasized “respect” or “respected” (nine times) and “interpret” or “interpretation” (eight times).

Biden’s language centered on rights and individual protections. His most frequent terms were the “American people,” “people,” or “voters” (21 times), followed by “constitutional” or “Constitution” (16 times). Biden also focused on specifics more than the other two presidents: He emphasized “healthcare” or the “Affordable Care Act” (14 times, primarily when opposing the nomination of then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett), “rights” or “right” (12 times), and “fair” or “fairness” (nine times). This vocabulary reflected his dual focus on procedural legitimacy and concrete policy stakes.

Thus, whereas Obama focused most on a nominee’s qualifications to be a justice, Biden and Trump were more focused on what the nominee would do as a justice: whether in adhering to an originalist judicial philosophy (in Trump’s case) or advancing democratic legitimacy (in Biden’s case).

Temporal and historical references

The presidents also differed in their use of historical grounding. Obama referenced the founders or framers sparingly (three times) and invoked historical examples moderately (five times, including President Ronald Reagan and Civil War era references). Biden made even fewer references to the founders (two instances) but emphasized Senate confirmation history and electoral precedent (eight examples of historical precedent) – perhaps not surprising given his long tenure in Congress. His rhetoric thus focused primarily on present-day policy implications rather than constitutional history or future projections. Trump most frequently invoked historical authority with references to the founders or framers (six times), made multiple mentions of Reagan (four times), and frequently invoked conservative justices such as Antonin Scalia (seven times). This pattern again aligned with Trump’s overall originalist framing.

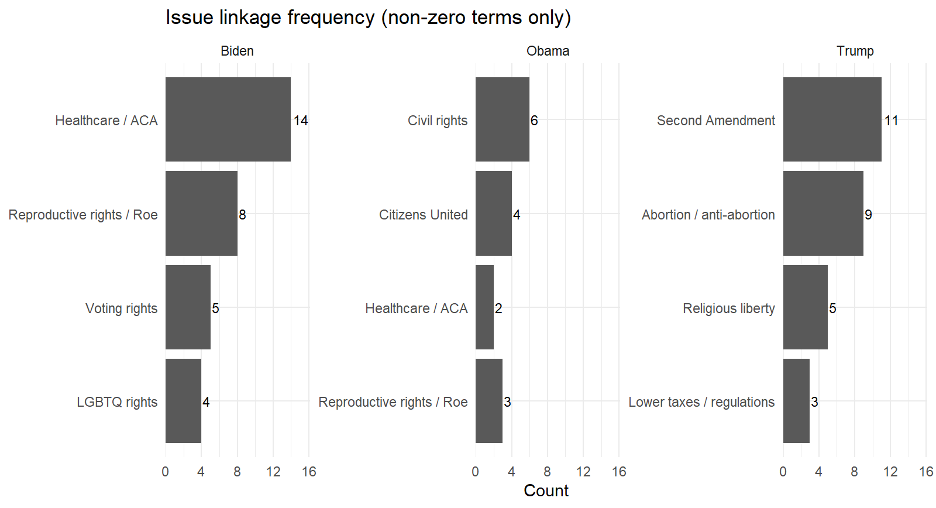

The presidents also varied significantly in connecting court nominations to specific policy outcomes. Obama made moderate policy connections, mentioning Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (four times), civil rights (six times), reproductive rights (three times), and healthcare or the Affordable Care Act (two times). He typically framed these as the court “standing up for” rights rather than direct policy outcomes.

Biden showed the highest policy linkage – a great deal more than Obama – emphasizing healthcare or the ACA (14 times), reproductive rights or Roe v. Wade (eight times), voting rights (five times), and LGBTQ rights (four times). This explicit connection between judicial appointments and immediate policy consequences distinguished his approach.

Trump again made direct policy commitments tied to originalism, discussing the Second Amendment (11 times), abortion or anti-abortion positions (nine times), religious liberty (five times), and lower taxes or regulations (three times).

Pronoun usage and audience orientation

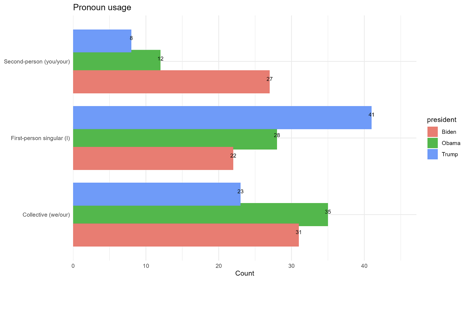

Pronoun patterns also revealed different rhetorical stances. Obama used first-person singular pronouns (28 instances of “I”), collective pronouns (35 instances of “we” or “our”), and second-person pronouns (12 instances of “you” or “your”), seemingly trying to be as inclusive as possible.

Biden employed the first-person singular (22 times), collective (31 times), and notably high second-person usage (27 times). This pattern reflected his emphasis on direct audience engagement, in an attempt to make a direct appeal to the voters.

Trump showed, by far, the highest first-person usage (41 instances of “I”), moderate collective pronouns (23 instances of “we” or “our”), and minimal second person (eight instances of “you” or “your”). This emphasized his personal decision-making authority and power to select the nominee of his choice.

Barack Obama: empathy within legal excellence

Obama’s most distinctive rhetorical contribution was articulating a role for empathy in judicial decision-making. In announcing Merrick Garland’s nomination, for example, Obama called him “an extraordinary jurist who is indisputably qualified” with “a spirit of decency, modesty, and even-handedness.” Obama’s March 2016 weekly address emphasized that Garland had “earned the respect of both Democrats and Republicans.”

A 2008 debate statement captured Obama’s judicial philosophy: he sought justices who “have an outstanding judicial record, who have the intellect, and who hopefully have a sense of what real-world folks are going through.” This “real-world” understanding represented a departure from purely technical legal competence. Two decades ago, in Obama’s 2005 Senate speech opposing John Roberts, Obama articulated his famous formulation: “95 percent of cases” follow clear legal rules, but in the crucial “5 percent of hard cases, the constitutional text will not be directly on point” and “the critical ingredient is supplied by what is in the judge’s heart.”

When opposing Samuel Alito’s nomination in a speech a year later, Obama also used politically charged rhetoric: According to him, “[i]n almost every case, [Alito] consistently sides on behalf of the powerful against the powerless; on behalf of a strong government or corporation against upholding Americans’ individual rights.” This framed judicial selection as inherently about whose interests the court would protect, not merely about legal methodology.

Donald Trump: originalism and transparent commitments

While running for office the first time around, perhaps Trump’s most significant innovation was releasing specific lists of potential Supreme Court nominees. In the Oct. 19, 2016, debate, he stated: “I feel that the justices that I am going to appoint – and I’ve named 20 of them – the justices that I’m going to appoint will be pro-life. They will have a conservative bent. They will be protecting the Second Amendment. They are great scholars in all cases, and they’re people of tremendous respect. They will interpret the Constitution the way the founders wanted it interpreted.”

Trump’s July 2018 announcement that he was nominating Brett Kavanaugh to the court emphasized constitutional fidelity: “I chose Justice Gorsuch because I knew that he, just like Justice Scalia, would be a faithful servant of our Constitution.” Trump made note of Kavanaugh’s own judicial philosophy: “A judge must be independent and must interpret the law, not make the law. A judge must interpret statutes as written. And a judge must interpret the Constitution as written, informed by history and tradition and precedent.”

For Barrett in Sept. 2020, Trump used superlative language, calling her “one of our nation’s most brilliant and gifted legal minds” with “unparalleled achievement, towering intellect, sterling credentials, and unyielding loyalty to the Constitution.” He also detailed her academic achievements, noting that she had “graduated first in her class” and received “the law school’s award for the best record of scholarship and achievement.” And, as with his other nominees, Trump expressed that she would “decide cases based on the text of the Constitution as written.”

Trump’s rhetoric to interpret the law as written contrasted significantly with Obama’s reference to “what is in the judge’s heart.”

Joe Biden: democratic process and rights protection

Biden’s rhetoric centered heavily on what potential justices would decide and the legitimacy of the process in naming them. In September of 2020 he addressed this directly with respect to Barrett’s nomination, contending that she had “a written track record of disagreeing with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision upholding the Affordable Care Act.” The Sept. 29, 2020, debate featured his repeated refrain: “The American people have a right to have a say in who the Supreme Court nominee is and that say occurs when they vote for United States Senators and when they vote for the President.”

Biden further called Barrett’s rushed confirmation “an abuse of power” and emphasized that it violated Senate precedent. His Oct. 26, 2020, statement characterized the confirmation as occurring “in the middle of an ongoing election.” (Although, notably, in the Sept. 29 debate, Biden said of Barrett personally: “I’m not opposed to the justice, she seems like a very fine person.”)

When announcing the nomination of Ketanji Brown Jackson to the court in Feb. 2022, Biden focused on her “exceptional credentials, unimpeachable character, and unwavering dedication to the rule of law.” He highlighted her “broad experience” across multiple legal roles and her “bipartisan” confirmation history. And Biden had previously made the historic significance of such a justice explicit (as described more below): “As everyone knows – I have made it clear that my first choice for the Supreme Court will make history as the first African American woman Justice.”

Comparing presidents

So what are the takeaways? I think this is best seen in three areas: the role of constitutional philosophy, the president’s political strategies and base mobilization, and the importance of identity and demographic framing.

The role of constitutional philosophy

Obama articulated living constitutionalism implicitly through an emphasis on judges understanding societal context and protecting vulnerable populations. His language suggested that constitutional meaning evolves through applications to new circumstances. The “percent of hard cases” formulation acknowledged that legal texts sometimes require judges to exercise judgment informed by their own values and their decisions’ real-world impacts.

Trump explicitly championed not outcomes but methodology, and specifically originalism, repeatedly stating judges should “interpret the Constitution the way the founders wanted it interpreted.” His campaign materials emphasized selecting judges who would “uphold the principles of the U.S. Constitution” as understood in originalist terms.

Biden focused less on constitutional theory than Obama or Trump and more on institutional legitimacy and concrete rights. His emphasis on process – ”the people should speak”—and specific policy outcomes (healthcare, reproductive rights) suggested a pragmatic approach that measured judicial appointments by their likely impact on Americans’ lives rather than abstract interpretive methodology.

Political strategy and base mobilization

Obama’s strategy emphasized consensus and competence to appeal to both moderates and legal elites, reflected in his emphasis on nominees’ qualifications to the Supreme Court. Garland’s selection – a moderate once praised by Republicans – exemplified attempted bipartisan bridge-building (though it ultimately failed to accomplish this).

Trump took a very different approach, explicitly mobilizing (potentially skeptical) conservative voters through transparent commitments on specific issues (abortion, guns, religious liberty). The nominee lists provided unprecedented accountability and clarity. His campaign emphasized that judicial appointments would be reserved for originalists and made the court’s composition a central campaign issue.

Biden adopted a dual strategy, trying to carve out a middle way between Obama and Trump: He opposed Republican nominees on procedural grounds (timing, process) while emphasizing concrete rights threatened by conservative court majorities. For example, Biden’s healthcare focus in opposing Barrett directly mobilized voters concerned about the ACA. And for his own nominee, Jackson, Biden combined historic representation with broad credentials to try and energize the Democratic base.

Identity and representation framing

Which brings us to the final category: identity (and qualifications). Obama explicitly acknowledged such considerations when nominating Garland, stating in 2016: “I appointed a Latino woman and another woman right before that, so, yeah, he’s a white guy, but he’s a really outstanding jurist.”

Trump emphasized merit (like Obama) but also noted demographic milestones. For Barrett, he highlighted that she would be “the first mother of school-aged children ever to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court.” And while much of Trump’s rhetoric focused on judicial philosophy and credentials rather than identity, even he acknowledged, in 2020, that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s replacement would “most likely” be a woman.

Finally, Biden made historic representation central and explicit – even more so than Obama. His campaign promise to nominate the first Black woman justice became a defining commitment. When announcing Jackson, he celebrated both her historic significance and her extensive qualifications, presenting these as mutually reinforcing rather than in tension.

Conclusion

Quantitative and qualitative analysis reveals three distinct rhetorical approaches to Supreme Court nominations. Obama’s language emphasized what I have called empathy within excellence, focusing on both his nominees’ qualifications and their ability to understand the real-world impacts of their potential decisions. His vocabulary centered on merit, experience, and independence. Biden’s rhetoric prioritized democratic legitimacy and rights protection. Trump’s language explicitly championed originalism and conservatism, while providing unprecedented transparency into his potential choices for the court.

These patterns reflect fundamentally different visions of the court’s role. Obama’s “5 percent of hard cases” acknowledges discretion and the need for empathy in the application of legal principles. Biden’s emphasis on “the people should speak” focuses on democratic input and immediate policy consequences. And Trump’s call to “interpret the Constitution the way the founders wanted” appeals to originalist theory and the conservative legal movement. As the court’s composition continues shaping U.S. law and society – and as talk intensifies concerning a future opening on the court – presidential rhetoric around its nominees remains a crucial window into competing constitutional visions and the evolving relationship between law, politics, and democratic governance.

The post Presidential rhetoric and Supreme Court nominees appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

https://www.scotusblog.com/2026/01/presidential-rhetoric-and-supreme-court-nominees/ January 14, 2026 at 10:17AM.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment